Saint Sebastian and Venice

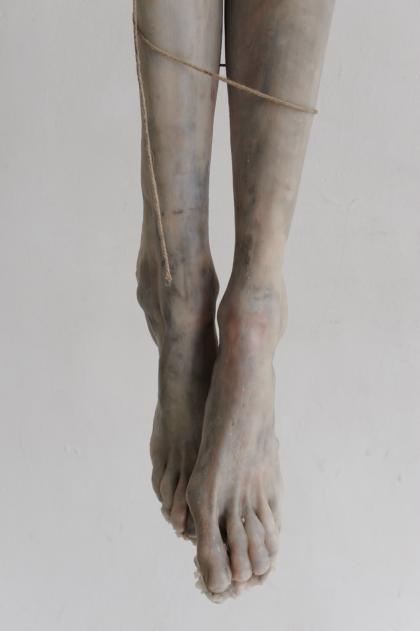

The exhibition opens with the monumental tree San S, in which wood, iron, bronze, wax, blankets and metal awls are fused into a skin of mystical pain. The martyred body of St Sebastian – traditionally shown serene, pierced with arrows against a tree – seems here to merge with the elm stump itself: bark becomes skin, and scars turn into sensual openings.

“I don’t shy away from the wound; suffering, decay, death and loneliness are as much a part of my work as they are of life. But the same goes for tenderness, connection, vitality and lust.”

– Berlinde De Bruyckere

With this work, De Bruyckere alludes to the Venetian devotion to San Sebastian, protector against the plague, who – immortalised in polyptychs by Italian masters such as Bellini and Titian – became a symbol of hope in a city once ravaged by the Black Death. For the Venice Biennale in 2013, De Bruyckere created Cripplewood, a work that again bears the traces of Sebastian. Too imposing for Bozar, yet unmistakably rooted in the visual tradition of the city on the water.

Renaissance painting

We remain in Venice. Another dialogue in Khorós seems to refer to the work Cristo morto sorretto da un angelo (c. 1502-10), previously attributed to Giorgione. The painting served as the starting point for her exhibition City of Refuge III (2024), created for the Venetian basilica of San Giorgio Maggiore. De Bruyckere transforms the Renaissance angel into a nameless being, wrapped in heavy animal hides and imbued with human vulnerability. Beyond its religious origins, the angel acquires a new, earthly and universal character.

During the coronavirus pandemic, the figure of the angel became, for De Bruyckere, a metaphor for caregivers who literally and figuratively carried the sick. Especially for Bozar, she has placed the archangel on a column of ancient wood. In wall-mounted showcases, fragments of wax, branches and flayed skin appear as contemporary relics: a tribute to Saint Benedict’s penance, as depicted in Albert van den Brulle’s 16th-century choir carvings in the Venetian basilica.

Enclosed Courtyards

The Enclosed Courtyards are small 16th-century mixed-media retables created by nuns. Flowers, fruits, and other paradisiacal symbols grow in their luxuriant miniature gardens –intimate sanctuaries, sealed off from the outside world.

Berlinde De Bruyckere first encountered these courtyards in 2016, and their fragile beauty captivated her instantly. The influence of these quiet, devotional spaces is evident in two works from the exhibition. Peonies [Pioenen] is a five-metre-long wall panel in which red peonies rise from layers of wax and floral wallpaper. The cabinet It Almost Seemed a Lily combines lead, iron, wood, wax and animal hair. The historical courtyards, with their layering and excess, find a contemporary echo in De Bruyckere’s work, which, layer by layer, enters into a silent dialogue about vulnerability and strength.

Lucas Cranach the Elder

One of the most powerful dialogues in Khorós is with the work of Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553). His Salome, draped in an exquisite gown, poses almost impassively as she carries the severed head of John the Baptist – a gruesome yet poetic contrast. Cranach reveals how beauty and violence are inextricably linked. That same duality echoes again and again in De Bruyckere’s work.

“I was particularly fascinated by the way he painted skin. So luminous and lifelike and with beautiful transparency.”

– Berlinde De Bruyckere

She is also inspired by Cranach’s distinctive rendering of translucent skin. De Bruyckere has developed a unique technique for her own sculptures: building up successive layers of wax in silicone moulds to create a delicate, marbled texture.

Francisco de Zurbarán

Is Lost V a subtle nod to Francisco de Zurbarán (1598–1664)? De Bruyckere has already expressed her admiration for the Spanish painter in To Zurbarán (2015), and Lost V (2021–2025) also reflects that fascination. A small, motionless foal lies on a sleek marble table. The sacred stillness of the sculpture evokes the quiet solemnity of Zurbarán’s Agnus Dei – the silent sacrificial lamb. The cold marble contrasts sharply with the weathered blanket that shelters the animal, highlighting the tension between rough hardness and vulnerable tenderness.

“Instead of a ‘retrospective’, I found it interesting, at Bozar’s request, to look back at dialogues and inspiring figures. As a result, my works, and their layering, read differently.’

— Berlinde De Bruyckere

You can visit and read Berlinde De Bruyckere. Khorós until the end of August at Bozar. The exhibition catalogue is available in the Bozar Bookshop.